Book Review -

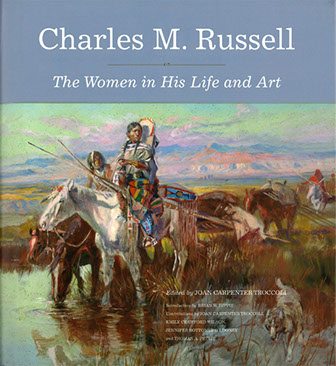

Charles M. Russell: The Women in His Life and Art

Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly, Summer 2019

by Mary P. Donahue

If Charles M. Russell had been born a few generations earlier, he might have been a fur trader like his great uncles, William and Charles Bent, the brothers of Russell’s grandmother, Lucy Bent Russell. The Bent brothers were legends in the fur trade—the founders of Bent’s Fort, the largest trading post on the Santa Fe Trail. William Charles M. Russell’s great grandfather, Silas Bent Jr. had dealings with Lewis and Clark in mapping the Louisiana Purchase. This western wanderlust in more than a few stories had no doubt trickled down to Charles M. Russell as he came of age in the last decades of the Old West and experienced it for himself as he worked ranching jobs in Montana.

A good majority of the work of the cowboy artists such as Russell and Remington was just that—boys, men and the drama of their action with each other, guns, animals, and the western landscape—galloping horses, flailing arms, dust flying, and the fading light of the sun… and the tenacity to hold on to a way of life. But as the saying goes, along with a great man there are great women… and as Ginger K. Renner first observed in her 1984 essay, “Charlie and the Ladies in His Life,” few artists of the West produced as many artworks depicting women as Russell.”

Charles M. Russell: The Women in His Life and Art shows the influence of women on his work and the resulting imagery. This catalogue and collection of insightful essays accompanied the exhibition of those collected works. The book’s generous color plates and photographs give visual emphasis to the words.

The first section, “Charles M. Russell’s Women: Reality, Convention, and Imagination” by Joan Carpenter Troccoli, traces Russell’s history of the real women in his life and the connection to his many works where women were the main subject. Foremost of these women is his wife, Nancy Cooper, who was the force behind his artistic career. Oddly, though Nancy served as a model for him, there are few paintings of her and few paintings of contemporary white women in general and these works are included. He prefers to focus on Native American women, albeit in a stereotypic and sentimental fashion. But as Troccoli writes “the stereotypes are themselves revealing of the complexities of history, culture, and the artist himself.”

The second essay, “Of Fantasy and Fiction: C.M. Russell and the Female Form,” by Emily Crawford Wilson, explains the artistic and cultural context of the female form in Russell’s time and shows its direct connections to Russell’s women subjects—idealized, exotic, and sometimes seductive. Yet, there’s hope! Russell’s illustration in 1904 for a book by Francis Parker, Hope Hathaway: A Story of Western Ranch Life, show an intrepid and skilled modern woman, on her horse, gun blazing just like the boys.

Jennifer Bottomly-O’looney’s essay, “Lela Roberts’ Oddly Sentimental Remembrance of Charlie Russell,” creates a view, through the life details and objects of one family, (like Charlie Russell’s burnt cigarette butt and match which Lela saved) into the early settling of Montana and, in turn, the development of Charlie Russell as a successful western artist.

The last essay by Thomas A. Petrie, a force behind the idea for this exhibition and catalogue, is “Life in a Double Harness: Reflections on Nancy Cooper Russell.” The focus is on Charlie Russell’s wife, obtaining “insight into the character and talent of the woman who idolized Charles M. Russell and branded him as an American art hero.” Their connection to Glacier National Park where they had built a cabin shortly before its designation and the powerful influence of that wilderness and solitude would lead Russell to his most productive period and best work of his life. Nancy’s honest recounting of their experiences provide insight, as does much of this well-done book, Charles M. Russell: The Women in His Life and Art, into the artistry and promotion in the partnership of Charles M. Russell and the most important woman in his life, Nancy Cooper Russell. It is an engaging and detailed look at an artist and artwork concerned with “The West That Has Passed,” admitting this great love affair had, at its heart, a woman.

The reviewer is a professor of art at Chadron State College in Chadron, Nebraska. She is a painter, writer, and explorer of western landscape. Her work can be viewed at marypdonahue.com. She was a wagon train extra in the recent Coen brothers’ film, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. onthetrailwithbscruggs.wordpress.com